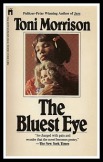

Claudia at The Bottom of Heaven kindly invited me to blogging event around the 40th anniversary of Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye. I was thrilled to participate. It is one of my favorite books. I had wonderful experiences with it as a student and later as a TA, teaching it to undergraduates in a women’s studies course. Although I am not a literary scholar, I deeply appreciate the symbolism and metaphors used in this book. It was where I first experienced quality classroom learning on issues of race, class, and gender; and the first time I learned to facilitate those discussions. Without question, I wanted to celebrate this with Claudia and the other bloggers.

At the end of The Bluest Eye, Claudia describes Pecola as a contrast:

“All of our waste which we dumped on her and which she absorbed. And all of our beauty, which was hers first and which she gave to us. All of us – all who knew her – felt so wholesome after we cleaned ourselves on her. We were so beautiful when we stood astride her ugliness. Her simplicity decorated us, her guilt sanctified us, her pain made us glow with health, her awkwardness made us think we had a sense of humor. Her inarticulateness made us believe we were eloquent.  Her poverty kept us generous. Even her waking dreams we used – to silence our own nightmares. And she let us, and thereby deserved our contempt. We honed our egos on her, padded our characters with her frailty, and yawned in the fantasy of our strength.â€

I think a lot about this passage because, to be frank, I just don’t know.

Let me tell you what I mean. I have this colleague or friend or relative who lives in another U.S. city. It can be anyone of those gleaming metropolises far away from The Deep South, a place that already feels a bit superior simply for not being a slave state 150 years ago. Maybe New York. Or Providence. Boston, San Francisco, Chicago or Philadelphia. Like many, these folks from Minneapolis or Seattle or Bangor are caring and giving. They were shocked when New Orleans was devastated. They click their tongues in worry about people on rooftops and trapped in attics. They try not to show their disgust when they see the grunge and filth around the edges of those images. It’s not that they are being, you know, judgmental; it’s just that they, personally, couldn’t imagine living that way.  But they do care, so when their church started gathering supplies to send, they gave. And when that same church brought down a group of do-gooders to rebuild homes, they came. “We came and built a house on a street that was just terrible,†she or he or they will tell me, “there wasn’t anything left on that street, it was just a mess.â€Â And then, the surprise, “but you know, I recently saw a picture, and that house we built? Well, know there are four more and you wouldn’t even know it’s the same street!â€Â They tell this story with pride and surprise at what can happen when do-gooders get together. “It’s really an example of the power of people, you know?â€Â Also, they watch Treme. So between the show and that house they built, well, they really get New Orleans.

“Her poverty kept us generous.â€

That passage sticks with me because when I’m faced with those situations from my story above, I don’t know what to do. I am thankful, without question. Please don’t doubt for a second that I am so, so thankful to each and every person who thinks about New Orleans. The people who watched those days unfold with us just as sick and angry as we were, and were so thoughtful and kind. I am grateful that folks are monitoring the oil spill and wondering about the coast. That is for sure.

But also? When I hear those stories above? I sort of want to be sick. I want to serve back their superiority on a plate of snappy come-backs. I don’t want to be in a place that is pitied. And frankly, after all I’ve seen, done, heard, and lived in this place, I know that it is not a place to be pitied, period.

“And she let us, and thereby deserved our contempt.â€

When something terrible happens, something so awful that our common humanity compels us to act on it – why does this become a source of pity? Before September 2005, no one cared of the poverty and inequalities that existed in the Lower 9th Ward, in Gentilly, in the Treme — places that now hold the collective imaginations as symbols of endemic and systematic disparity. The poverty set the stage for the disaster, yet did not compel true action until it became a spectacle. And then, it became a place of pity.

Why?

Claudia discussed this with me as I was struggling with ending this piece. In an email, she wrote:

How can we assist people and populations in need with mutual respect (and empathy? openness?) right now, in 2010, without using their suffering to affirm our own sense of virtue and self worth? And perhaps, more controversially, how do those of us whose way of life has been weakened and is in need of repair, accept help appreciatively, but in a way that makes pity and contempt unwelcome? (That line – “and she let us, and thereby deserved our contempt” – is arguably one of the most haunting and most troubling in the book! How did Pecola “let” them? Through silent acquiescence?) Maybe the answer begins in breaking silences, naming these awful, awkward moments, and how much of our well-being is based on the illusion of “us” vs. “them.”

Within this context, part of the legacy of The Bluest Eye is in this complex issue of giving and receiving. Disasters of unthinkable proportions will continue into our future, compelling people to act. Is there a line between curiosity over an event so monumentally catastrophic that it must be seen to be understood – and respect for those who are living through it?

As for naming those silent, awkward moments… I agree that it is important. But then what do we do? Breaking the illusions of “us” and “them” means that we all take some responsibility for the inequalities in the world… and then make the hard choices required to address them. And this, unfortunately, seems like something we will still be discussing when The Bluest Eye celebrates another 40 years.

What do you think?

(Thank you, Claudia, for the invitation to participate!)

Painted Maypole | 12-Jul-10 at 2:18 pm | Permalink

I read this book about 6 or 7 years ago, when a parent refused to allow her child to read the book in class for a public school, and it was all over the local news (in Bakersfield, CA) It was hauntingly beautiful, and so challenging, and I wanted to punch that mother for not allowing her child to read it. erm, but I’m not violent. 😉

your ties of this with Katrina, and other disasters, are interesting. It was amazing how short lived most people’s interest in the disaster was. I remember 6 months after Katrina going to CA, and everyone asked, but 98% didn’t want to hear the real answer. I I DON’T think the questions of race and inequality have been well addressed. They have been forgotten and pushed aside for more pressing matters… like celebrities and sports and what’s the latest style.

De | 13-Jul-10 at 7:11 am | Permalink

I was thinking about this yesterday, though I didn’t think I’d have a comment. It is a complex issue, and I haven’t read the book. However, last night in the book I am currently reading, Weekends at Bellevue, by psychiatrist Julie Holland, these behaviors were framed as a cultural response to insanity. She writes:

“…we hate to see things in others that we don’t want to see in ourselves: weakness, need,despair, aggression. We should be compassionate to those who stumble out of our lockstep. Yet in our culture, the mentally ill are demonized and shunned. They are ostracized and marginalized as a by-product of our primal fear of going crazy ourselves. It is the nightmare of our own “shadow self,” as Jung called it, that allows us to treat others so harshly.”

nonlineargirl | 14-Jul-10 at 9:10 pm | Permalink

There is something in human nature that craves the distinction between us and them. From young kids being obsessed with whether people are male or female, to the hundreds of years of enmity among people in various countries (take your choice – any country with multiple ethnic or social groupings and a long history). I am not saying it is good, but it is something that takes training to get past.

holly | 14-Jul-10 at 9:24 pm | Permalink

Yeah, I think this is true. We like to figure out what our differences are, discover our uniqueness and similarities as ways of figuring out ourselves. But as we age, I don’t know if it’s a training thing or a safety thing that we begin putting value into those differences. It’s much safer to think that we’re different from someone — we won’t get XYZ or whatever — than consider our own risks.

holly | 14-Jul-10 at 9:33 pm | Permalink

With that context, I’d be curious to what you think of the book. It’s a brilliant book for how it sympathizes with the characters on an individual level (something Jung-type theory would relate to) and the metaphor of the social and political context, which frames the entire scenario.

holly | 14-Jul-10 at 9:38 pm | Permalink

WOW… do not read list. Frightening.

I think it’s too hard for folks, in the midst of busy lives, to think about pressing issues that feel so removed from their daily lives. We all feel so powerless… so why bother? I can appreciate this feeling. What I wonder is what we have to do to get past this… what would allow us to feel involved and powerful not only in our own lives, but in the functionings and happenings in the world?

Missionaries to the Gulf « NOLAFemmes | 15-Jul-10 at 11:11 pm | Permalink

[…] domestically and internationally, this is a big topic of my profession — and something I write and think about often, particularly after living through the summer of 2005 and the experience of being in a […]