{ Category Archives }

Issues

October Awareness: Breast Cancer and Hispanic Heritage

Tina asked for bloggers to participate as guest bloggers for October, on the theme of Breast Cancer Awareness, in honor of her Mother, a breast cancer survivor. Here is my cross-listed post.

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month. It is also Hispanic Heritage Month.

And breast cancer is the leading cause of cancer death among Hispanic women.

The Hispanic population is the largest minority group in the United States. Hispanic Americans make up roughly 14 percent of the U.S. population, but they are the fastest growing segment, estimated to reach 20 percent or more by 2050.

Even when access to health care is adequate, for Hispanic women in the United States, breast cancer is more often diagnosed at a later stage, when the disease is more advanced.  Further, approximately two-thirds of breast cancer found in Hispanic women is discovered by accident – not by screening or mammogram.

Actually, according to a Kaiser Permanente study, the news gets worse. When compared to non-Hispanic white women, Hispanic women are more likely to be diagnosed at a younger age, have cancer that has already spread beyond the breast, have tumors with cell type that have a poorer prognosis, have larger tumors, and have tumors that cannot be treated with some of the most effective medicines.

What’s the public health response? Interventions aimed at increased screening, access, and education. But is it enough?

If early detection and survival is the goal of Breast Cancer Awareness Month – then there has to be a conversation about an individual’s ability to access health care information and services. Central to that conversation is the reality that those very life-saving information and services are unjustly linked to one’s racial, ethnic, socio-economic, and immigration status.

How do these dynamics play out? Here is a local example. If a woman cannot demonstrate access to or eligibility for some type of insurance (or have the ability to pay) – programs can deny her a screening for breast cancer. Why? The argument is that it is unethical to provide a screening for a disease when the patient will not be able to access treatment for it. In the past year, one of the screening programs in New Orleans was shut down for this reason.

What is more unethical? Denying screening? Denying treatment? Or needing any of coverage or eligibilities in the first place?

The bottom line is that women in our largest ethnic minority group do not have a good outlook when it comes to breast cancer.  And improving the outlook is about more than screening programs and access to medicines. Striking at the heart of a serious disease means a serious look at our entire system of care and asking where treatment for breast cancer and survival of women lie within our values.

Of Two Minds

In class on Tuesday, I showed students part of a documentary film called SASA! about the interplay of violence and HIV in women’s lives in Uganda and Tanzania. Sasa means “now” in Kiswahili (the Bantu language most of us know as Swahili) and was chosen as the name of the film to emphasize the need for knowledge building about how violence, disease, and cultural power dynamics impact women. The organization that worked to create the film, Raising Voices, is a respected NGO working in non-violence, specifically regarding women and children. The film itself was made by The People’s Picture Company in partnership with Raising Voices.

The film follows the stories of women who have been personally impacted by violence and HIV. Their lives illustrate the common barriers women face to health and personhood. The issues are not particularly unique to this one place nor are they revolutionary in terms of what we already know about women, poverty, and heath — but they are still tremendously tragic. Bride prices, cultural expectations, personal beliefs of a woman as economically dependent, social acceptance of plural marriage… when these are combined with violence and poverty, disease is not far behind.

(Quicktime 30 minute film here.)Â SASA (30 minutes)

I was surprised at how much of the material discussed in the film came as a surprise to students, or at least, that they showed such great pain at the realities in the film. I had been taking it for granted that these were things everyone knew about women in poverty: that their lives are characterized by great abuses and limitations that are unthinkable to women raised in the West. In fact, I usually am frustrated by the over-characterization of ALL women, particularly AFRICAN WOMEN, of living these oppressed lives. Films like this often frustrate me because I feel it gives us wealthy Westerners reason to pity women who aren’t like us, infantilizing their lives and experiences in patronizing, imperialist ways. I’m more comfortable talking about strengths, resistance, community building, and learning. These sort of films and stories can paints the picture that women, even women within these terrible circumstances, are completely passive — controlled by the whims of their fathers and husbands — providing no self-directed action toward any part of their lives. In depth research into these issues shows us that women who we view as the most “oppressed” by our definitions of oppression still act in resistance in ways that we might not see or appreciate. Those are the sorts of conversations I like to have. Let’s talk about what works and build on it.

But this class is an overview class. Many students within it have never been outside of the United States, least of all to a non-OECD country. First, then, they learn of the realities of poverty. Thus, the film. Thus, the discussion.

It was a good class, a fine, interesting discussion. But it left me a bit raw. I’m not sure how to teach an introduction to the realities of global poverty without painting the “woe is me” picture. Is there a way to tell a tragic, terrible story, showing relevant barriers and challenges without painting a picture of a passive victim and active perpetrator? I tried my best to break up that binary dynamic, about how the limits on one equally limits and defines the other – if you define one as black, then by definition the other one is completely white, leaving no room for gray. I tried to walk that line of breaking thought out of submission versus aggressive, masculine versus feminine, victim versus perpetrator… but who knows how far that was absorbed.

Maybe it’s just that easy to believe that men are assholes? Or, maybe it’s easier to believe that women are passive, submissive, and silent.

Donors do like a good victim story, after all.

Still, I like this film. I think it does a good job of showing the problems and gives focus to how the community is coming together in their own terms to deal with them. It does an excellent job of showing the ridiculousness of the “ABC” approach and how utterly useless it is in women’s lives. (The ABC approach is the “Abstinence, Be faithful, use Condoms” approach to HIV prevention. You might as well tell women that drinking Kool-Aid will prevent HIV. Actually, the chemicals in Kool-Aid are probably more effective in limiting HIV infection than ABC. But I digress.)

It ends in a positive light, showing the impact of peer counseling and community work. And of course it does! Because ultimately the film needs to show interest and build compassion. Ultimately, this is an agency that relies on donations. It is a wonderful organization doing work I respect and admire. The sort of place I’d love to work, actually. When you think about it, they tread a fine line in this film: showing just enough compelling story for donors and then showing the proactive ways a good organization can be capable of improving even the most difficult of lives.

So why do we focus so much on all that terrible, victimizing stuff? What is it that is so compelling? Is it the same thing that makes us listen harder when the neighbors start to fight, or slow down to look at the scene of a traffic accident? Do the realities of living in poverty provide good voyeur material?

I can’t help but feel a little frustrated. Maybe it’s that I’m jaded and tired of the essentializing of ‘women in the developing world’. Maybe I’m tired of seeing the same solutions for problems that seem never-ending.

In the end, I felt that putting it here might be a way to work it out. Maybe I’m wrong and there are very surprising things to be found in this film. Maybe I’m alone in my frustrations. And maybe there is more we can do?

April Just Posts for a Just World

Kate has been dealing with diarrhea for almost two weeks. It’s been a pain. She has an incident at school and is home for a day and nothing happens, then she goes back and the whole thing happens again… with an occasional blow out at home that results in floor, clothes, and bed washings. I’ve been able to take her to the doctor for tests, give her fluids, and not for a moment worry about any of it. The inconvenience of it all was in the back of my mind when I read Robin’s post for assistance. My friend, Robin (whom you may remember from her amazing Mama-multitasking) lives and works in Bangladesh. She works for ICDDR, B and recently posted a plea for support for her agency, which is struggling to get re-hydration salts to an impoverished population that will die without them. One of this month’s Just Posts is about poverty in Bangladesh and offers an interesting backdrop to the reality that Robin sees in her work — and what went on in my own head when I thought about how “inconvenient” diarrhea was for our family while others are facing it as a life and death situation.

Also? A package of oral rehydration salts costs about ten cents.

Just a thought. And on to Just Posts.

Thank you thank you thank you thank you to this month’s readers and writers and especially to the new folks who contributed to the April Roundtable… thank you. Be sure to stop by and say hi to my Just Posts Partner, Alejna, too!

April Just Posts:

- Amanda at Love Letters in Hell with I chose my choice!

- angielynne76 at Angielynne76’s Blog with Equality for All

- antiracist parent with Oprah and the secret lives of moms

- Ashley at The Dhaka Diaries with Faces of Poverty

- Emily at Wheels on the Bus with Bea and Eve

- erika at Be gay about it. with Marriage equality again — VERMONT!

and Marriage equality — IN IOWA!! - flutter with RAINN dance

- flyingtomato at flying tomato farms with the un-holiest marriage

and Quit calling me a “Hobby Farmer…â€

GirlGriot at If you want kin… with Will This Make My Mom an Immigrant and Ceremonies in Dark Old Men - Hispanic Fanatic with Prepare for Impact

- Holly at Cold Spaghetti with Where I Ponder Charity

- Julie at Using My Words with Breastfeeding is like five whole minutes of your life, total…so to speak

- Julie Pippert at Momocrats with Senator Roland Burris supports National Equal Pay Day, co-sponsors Paycheck Fairness Act

- Knitnut with A few highlights from Rethinking Poverty

- Mad at Under the Mad Hat with Dear John

- Phoebe at Rectory Entrance with How’s that Gentrification Going?

- Planet Nomad with Do They Know It’s Christmastime

- Quadelle with A mini home makeover

- Rae at Journey Mama with Thirteen Follows a Long Time After Twelve

- Thailand Chani with Susan Boyle and Necessary Rant

- The Painted Maypole with Ten

THANK YOU to April Just Post Readers:

Where I ponder Charity.

Right after All Things Considered, just moments before the classical hour begins, our local public radio station has the owner of a consulting firm give advice in minute’s time. They call it “The Louisiana Rebuilds Minute.” We call it “The WWOZ Minute.” (A friend coined the term, meaning that this is when he switches the radio to the local music station for that minute).

The idea of the Minute is that the people of Southeast Louisiana are too stupid to realize that it just takes a web search to find the answers to all problems related to an unprecedented rebuilding of an American city. Since we’re too idiotic to figure it out, The Minute does it for us. Paul and I have been joking for years that we would make a “Louisiana Rebuilds Minute” Generator — you just add in a common post-Katrina problem, throw in some patronizing ‘pull yerself up from yer bootstraps’ talk, and suggest that one consulting firm’s website has alllll the answers. Insert those few tidbits, press enter, and BOOM, you’ve got your manufactured minute.

The point that The Minute doesn’t get is that JUST BECAUSE there is one organization out there with funds to build playgrounds, doesn’t mean that every school that needs one and applies will get it. JUST BECAUSE one bus is available to a few folks who have the magic combination of ills and scripts to qualify for reduced medicines doesn’t mean that everyone who needs meds can get them. And JUST BECAUSE The Road Home offered funds to some families doesn’t mean they have all that they need to rebuild their homes and lives. Just because there are programs and grants and applications and dollars out there doesn’t mean that they are thought through, that they are honest, that they actual reach the people that they are meant to reach, and that they make any impact at all in the outcomes of our daily lives.

It is easy to get mislead.

It is easy to think that ideas are either good or bad.

I’m not so sure. If I have learned anything from being a part of New Orleans’ recovery, it is that EVERYTHING is mired in thick, silty gray.

And in the middle of all that mess sits Charity Hospital.

One of the big discussions flying around Southeast Louisiana surrounds Charity Hospital. Until Katrina, Charity was the second largest hospital in the country and one of the oldest continuously operating hospitals in the world. It was the primary source for health care for many of New Orleans’ poor. Actually, considering that many of Charity’s former patients have not seen a physician since Katrina, technically, Charity is still their source for health care… it’s just not open for them to receive it.

In fall 2007, Jim Aiken, the LSU University Hospital Chief of Emergency Medicine who worked the Emergency Department through Katrina and the aftermath, came to a class I was assistant teaching. His fascinating lecture included discussion of Charity’s pre-storm emergency plans, his experience of the storm and flood from within Charity, how he helped coordinate emergency care in the extended aftermath, and finally some of the issues involved with long-term planning for health care for the city. At every step, the issues are overwhelming at best — but what struck me was his passionate and pointed arguments for medicine, good medical care, and services to the community. He left me convinced that we need to rebuild a top-tier medical facility in this city, one that serves the poor within it, both because it draws good doctors to gain experience within it and because providing care to those who wouldn’t otherwise receive it is as important in this community as drinkable water and drivable streets.

A little over a week ago, the Schweitzer Fellows held our second symposium. This one was on “The State of Health in Louisiana” and Dr. Larry Hollier, chancellor of LSU health sciences center (encompassing the training programs for all allied health fields at LSU), was one of the speakers. His presentation was about the new LSU health sciences center — a center which is desperately needed, but is incredibly controversial in how it plays out.

The issue is that Louisiana’s doctors come from LSU graduates… by no small amount. The physicians practicing in the State are close to retirement age by overwhelming numbers, and the physicians coming out of LSU are not the type to stick around and take their places. Even before Katrina, LSU was seeing a substantial increase in the numbers of foreign-trained medical students who were ‘matched’ to attend LSU for their residencies — these are students who tend to go back to their home countries after residency. There were also increases in ‘matches’ with students for whom LSU was not a top choice… indeed, has not been a first choice for many in recent years. In addition to bringing in students who are not necessarily going to stick around… LSU has not been attracting the best talent, who are going to get picked up by the more desirable residency programs. Post-Katrina, these enrollment numbers have been even more dire, suggesting that the outlook for Louisiana to have competent, young physicians to support the State’s medical needs into the future is grim. Dr. Hollier argued that plans for a new science center were in place long before Katrina, and that the need for an expanded, updated center for treatment, training, and research was critical to the survival of health care in Louisiana.

And I believe him.

Don’t get me wrong: my impression of the guy was that we’d have some seriously different views on just about any medical or social issue… but the numbers and his argument was compelling. More than that, it completed echoed my experience as a student: my peers don’t stay. Heck, *I* am having trouble figuring out how we’re going to stay. Even if Paul had gainful employment, the fact is that the research dollars to study health inequalities in our city don’t go to researchers in New Orleans. If I want to stay involved in research here, it seems like I need to move to Chapel Hill or Ann Arbor or Boston or wherever in order to do it. (I’ll save this rant for a later date.)

I think that we need a commitment to a new, state-of-the-art facility to attract new talent, house research programs, and rebuild health infrastructure in the city.

Dr. Hollier spoke ONLY of the LSU plans — NOT the combined VA plans. In the LSU plan, only 33 homesites are impacted over an area that encompasses more empty parking lots than businesses or homes. (The VA plan, as outlined in a wonderful advocacy website, impacts many more people and historical properities.) He argued rationally that the Charity hospital building could not be retrofitted to the needs of the new center and any expansion did not include parking or other supportive infrastructure necessary for that sort of facility. He suggested the renovation of Charity as apartments for residents.

Everything that I know about New Orleans and the way things work make me question people in power — question their motives, question their reasoning, wonder about what they haven’t considered. (In contrast, it also has shown me that New Orleanians are some of the most change-resistant people on the planet… but possibly for good reason.) Yet, I am compelled to WANT this new center. I WANT a place where I can collaborate and build and learn and serve. I’m EXCITED about the possibility of this center… it makes me want to be here, stay here, work here.

Those first couple of blocks closest to I-10? The ones that are predominantly occupied by empty parking lots? I can’t think of a better use than to build a new science center.

But. The rest? Well. I’m uncertain about this. Because I feel that Dr. Hollier would drive through a community like lower Mid-City and not see a community worth saving. He wouldn’t necessarily see a pattern of New Orleans rolling over yet another predominantly African-American community for the sake of progress. Or, maybe he would — maybe he would but he would argue it was necessary for the common good. And sometimes? Sometimes I believe in the common good, even if it stomps all over individual rights. Early public health efforts involved holding people down for immunizations against their will… and that is WHY we were able to control disease. Sometimes common good is a good answer.

BUT! Common good should come out of insight and input from the community. That’s what it’s all about. I’m not convinced that LSU are taking alternative plans seriously. I don’t understand why the RMJM Hillier plan isn’t feasible and while I am not convinced it is the right place to go, I do think it signals to LSU that it needs to look for compromise.

And I’m worried that this will be locked in years of debate and at the end, the people of New Orleans will continue to suffer for lack of a comprehensive medical center and a generation of medical talent will slip through our fingers.

There is no easy answer here. And I’m sort of all knotted up inside over it because it involves my field (public health) and my passion (community-level advocating/organizing) — with one tromping on the other in the name of common good.

Got anything good for this one, Louisiana Rebuilds Minute? What website of yours solves this??

(If anyone still reading has thoughts, comments, insight, or ideas… I’d love to hear them.)

So, what is it that you do? Part One.

It’s dense, y’all. So here’s the first dose.

It’s about race and health in public health research.

The U.S. is a multi-racial, multi-ethnic society, so we use race as a variable in all of our research. We do this partially because of the fact that racial differences persist in virtually every area of health interest, and partially because of convention – we publish statistics stratified by race, we control for race in research models, and we exclude individuals from analysis on the basis of race. What we (‘we,’ meaning me and my colleagues of health researchers… if I might take that presumptuous leap of status) don’t do is stop to question whether race is really an appropriate construct – what it means, what it really differentiates, and what it ultimately suggests.

This is really important because the use of race in public health research is very problematic. The idea is that using race categories controls for some sort of undisclosed differences in population genetics… or in fancier talk, the epidemiologic assumption is that there is a genotypic difference that is being controlled. But in reality, researchers aren’t in the practice of, say, taking gene frequency measures in their participants. And more to the point: they aren’t even in the practice of defining the criteria for assigning a person in one racial category to another.

Well, if you’re still with me, you might be asking about the standard. Because, surely, our medical researchers have come up with some hard and fast rule about the biologic concept of race in medicine.

Nope.

And as much as population geneticists will jump up and down screaming about things like ‘continental racial categories’ and the higher incidence of genetically-related disease in certain groups (say, sickle cell) – the bottom line? All our genome work has us coming back again and again to say that genetically, we’re all pretty much the same.

Richard Cooper (an MD and Epidemiologist at Loyola Med School in Chicago) is sort of the Master and Commander of this discourse and I’d be remiss to try and restate what he says so darn clearly:

Racial differences reflect different social environments, not different genes, even where two groups live side by side, as do blacks and whites in the United States. Race does not mark in any important way for genetic traits; rather, it demonstrates beyond question the paramount role of the social causes. We have much more to learn from that paradigm, rather than the one offered by ethnogenetics.

In short, when we’re studying race, we’re really not studying genotypic differences – we’re studying phenotypic differences. (e.g.: the differences that result in our environments, not our genetics.)

Okay then, but public health uses race all the time and finds all sorts of interesting results. What does all that mean??

For one, it means that the results might be screwy. The majority of public health research occurs statistically: where a model full of complex and overwhelming Greek letters spell out a variety of things (the independent variables) that predict what happens to an outcome (the dependent variable). Race is most often used as a dummy, or binary, variable – meaning that you are either black or white – so the lack of conceptual clarity about what in the world each of those categories means leaves a great deal of room for error… if you aren’t controlling for something very clearly within your model, it means that your variable is open to error. It could be measuring the effects of other things in your model, including things in the error term. This means it could be “endogenous,†which, in public health research, is a Really. Bad. Thing. Suggesting that using race as a binary variable presents a problem of endogeneity to statistical models is sort of like saying that that ‘vegetarian’ gravy your Mom has been feeding you for all your 20 years of vegetarianism is actually made from 6 different animals. It ruins everything you’ve ever done with it and colors your ability to use it in the future. It’s better to just not know. Or to ignore the reality. Or! To reinvent it!

Like, for example, saying that race doesn’t really mean what we think it means. Let’s get real, you say, we know that race is all messy! So when we’re talking about race disparities in health, we’re actually measuring other things… you know, like socioeconomic status, discrimination, cultural factors, stuff like this that we know have a racial component.

That’s all fine and good, I answer, but public health models shouldn’t be proxy for anything not clearly defined. That’s not good science. It’s more logic to argue that if race is a proxy for other factors, then we need to find better ways of measuring those other factors. If we’re going to intervene effectively, we need to clearly understand what is going on.

Let me give an example. Let’s say that you are a health researcher and you’re studying prenatal care utilization. You’ve got a great regression model controlling for a variety of factors and your results show a statistically significant coefficient for the race binary variable (that the mean number of visits is higher for whites than for blacks, even when you’re controlling for things like income, age, insurance status, etc.) You might fall into the trap of reporting (as is embarrassingly common in published research) that “race is a significant determinant of prenatal care utilization.â€Â Think about that for a minute. The color of one’s skin has nothing to do with how many times someone sees the doctor. How the world around someone reacts to them due to the color of their skin (or other individual factors) may very well impact how many times they attend a prenatal visit… but that is not what the model is measuring, nor what the data is suggesting!

Further, if you go along that route, you may filter that finding down to medical and public health practice. It may be unintentional or even unrealized, but your intervention could be focused on race, trying to address whatever it is about being black that means you go to the doctor less. You may not even think to see what is going on with the doctor, or the clinic, or the system because you’re so focused on intervening in on that race factor… and you’d be missing the point.

Public health science needs better conceptual precision about the measurement of race, period. At the very least, the lesson here is that we need to be clear on what we’re measuring and how we’re interpreting it.

“Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing.” (Albert Schweitzer)

The year I struggled the most was right after college. I was working for the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington, DC, and had living expenses that were crippling. One month, desperate for a suit I could wear to some of awards ceremonies I had privy to attend, I purposely used my overdraft protection to write a check that I knew I couldn’t cover on overdraft — knowing that I was to be paid two days later and therefore would not bounce. That following month, already starting in the hole because of my $50 suit, I gave $10 to a co-worker in the mail room who was collecting money for his daughter’s school. Initially after I gave it, I regretted it. It was the same $10 that was suppose to be my lunch money for the next few days. But ultimately, when I thought about it, giving that money became one of my proudest moments. I’d be feeling so strapped for months — living paycheck to paycheck — and it made me feel better about my situation and myself to give to others. Didn’t Anne Frank say that no one ever became poor by giving?

I’ve written before about the importance of spending a little more to lend support to local organizations, local business owners, and local products. As 2008 drew to a close, I was thinking more and more about the things I’m most proud of this year and wanting to talk about giving… but I felt like it would come across as showy or superior, which is not how I feel about it nor how I want to come across. So I stayed quiet about things like money and giving. Then Jen and Mad posted about giving and encouraged it from others. So here I go.

I’m proud at how we give. And each year, we strive to give more. I’ve read a lot about folks trying to get back to basics, reusing and recycling, all that jargon that is so popular these days. But what about giving your time and money? That, in my opinion, is the giving that matters. If you’re just giving away stuff from your attic or closet or basement that you don’t use anyway, is it really an effort to be a better person and community member, or just to improve your own life? And while that’s good in it’s own place, what about setting examples for our children on giving more than our old things: our time, our attention, our energy, our talents, our hard-earned money… to help others? Isn’t teaching compassion and empathy the whole point of living simply — and if it isn’t, well, then shouldn’t it be?

This year, we gave more than 5% of our total income in cash donations, donated our services to local fundraisers, served on nonprofit boards, sponsored local events, volunteered on committees, showed up for work days, assisted with computer help to organizations and individuals, wrote grants, taught English, and offered translation. All of these called for our time and took us away from paying work. We don’t have money to burn or family inheritance safe guards. If we just had made our donations in-kind and saved the cash, we could have done all sorts of things we’d have loved to do: spent more time at the beach, gone to Disney World, finally replaced that 12 year old mattress with a king-sized set, upgraded my 6 year old camera, or hired help to finish some of the many renovations we’ve been working on for years. But we believe that the only way to give is to plan for it every month as a necessity. There is never enough for anyone to feel secure, it’s always that way. So giving has to be a priority.

No one has ever become poor through giving.

And really, what will happen if you gave an extra $20 or $50 or $100 a month? Would you starve? Would you lose your home? Because within that month, there are many many many many many in our world who will. What will you have lost? I’m not trying to be preachy… this is what I feel, what I say to myself when I feel frustrated or stretched thin or like I’m denying myself or my family things that could make our lives easier or brighter. Because in the end, we are better than great.

And ultimately, when we came to the end of the year, I didn’t regret the things I hadn’t bought or done. (Even if I still wish we had that big bed and am bummed that we are stepping over construction debris each day.) All that really doesn’t matter. Instead, I wished I would have given more during the year and encouraged others to do the same.

When you come right down to it, we live extravagantly compared to most of the world. So we should do more. There is so much more to do.

In the first few months of this year, we are giving monthly donations to Abeona House, the preschool we helped start after Katrina. While Abeona House is just one of the organizations we give to, it’s one of the ones closest to our hearts and the one we pledged to give the most to. Having helped start the organization, we know how it works, where the money goes, and how it is managed. We know that the people employed are being paid a good wage (although childcare professionals are paid a pathetically low salary across the board everywhere) and full-time employees receive benefits, which is rare in this field in our city. There are Abeona employees who lost homes in Katrina; one is still living in a FEMA trailer. Abeona is one of the only preschools in the city to offer a sliding scale tuition. Donations to the school help it offer placement to more lower-to-middle income families (teachers, social workers, nonprofit organization workers, artists) who would otherwise not qualify for State-based assistance programs. If you are looking for a 501c3 organization that will use your donation in the service of children’s programming and family support: this is one that applies.

Other organizations we feel similar about and give to are Ecole Bilingue (where our kids currently attend school) and Planting Magic Beans (founded and run by good friends of ours in Peru).

No matter what happens, I know that we will be okay in the ways that matter. And ultimately… No le hará rico; no me hará pobre.

Part of the Main

Despite my instinct to hurl whenever I start to feel sappy, I was and am very Thankful for many things today.

I am thankful that my children are asleep without hunger or fear, that we have good health, love for each other, and a community that fills us with friends and opportunities to enrich our lives. What more could we ask?

In a world filled with unspeakable horrors and inhuman poverty, we are beyond blessed: we are among the most privileged on earth. Chances are, if you’re reading this, you are too. The Global Rich List is a quick way to check.

If we, then, are the world’s wealthiest people, do we have any social responsibility to those less fortunate? Any moral directive?

I’ve blogged about my own beliefs on these things before; John Donne still says it better than I ever could.

It’s been floating around for awhile that those in the lowest income brackets tend to give more in terms of total assets than those earning significantly more. The percentage of giving falls dramatically at the household earning level of $100,000 per year and does not rise again until you reach the ultra rich categories ( >$10 million/year).

Here’s another thought. Is giving something that one should do because it makes the giver feel better about them self? Or should one give because it’s something we all have a responsibility to do? Is caring for and about each other a goal to be met, or an aspect of what makes us human?

So as I am thankful for the peace within my household tonight, I think of those who do not have rest. This global recession will impact the most vulnerable the hardest. Even as we tighten our belts and hunker down for an uncertain future, shouldn’t we also be talking about what we can do to take care of others? Next year, I want to be thankful for peace in households outside of my own, in places in the world I’ve never been, with people I’ve never met.

Blog Action Day (After)

Yesterday was Blog Action Day AND Love Your Body Day.

Augh! Both things I wanted to blog about. If this were back to the excuse letter, I’d say that I was at a Board Meeting last night for a nonprofit serving the under- and un-insured, and well, doesn’t that give me a little slack? “No,” says the calendar. Well, I’m not so good with following rules anyway, so here goes.

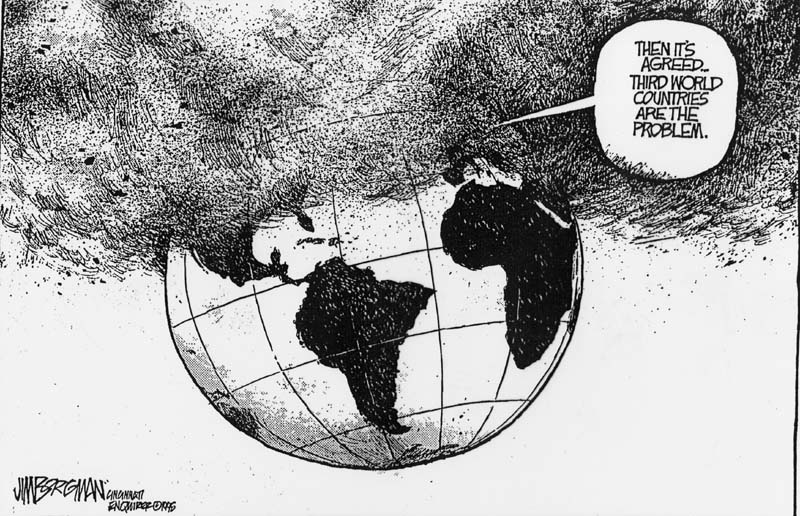

The theme for Blog Action Day was POVERTY and one of the reasons I felt compelled to write about it today is because of my great disappointment that no one spoke about it during the debate last night. The issue of poverty is so dear, so important to me that I’ve thrown myself at three degrees, two schools, a hand-full of countries and a ton of work so that I could understand it better. Here are two posts I’ve written in the past about poverty. Global poverty — the fact that 1 in every 6 people on the planet lives on less than $1 a day — is one of the most important issues for us to discuss. It impacts all of the other issues, things like terrorism, health, economics, and environment, that we are so concerned about in this election.

One thing that was discussed in last night’s debate that has A LOT to do with poverty are free trade agreements. In particular, the candidate’s discussed the Colombia Free Trade Agreement, which McCain supported and Obama (rightly) did not. Obama very nicely summed up his reasons for not supporting the agreement: there were no environmental and labor protections in it. The topic of free trade offers great entree to a discussion on poverty.

A Question: how do the free trade agreements supported and promoted by G8, IMF, WB, and most importantly the U.S. impact global poverty?

Answer: one heck of a lot, and not in a good way.

This article sums up the complex issues, ideologies, and major players very well. It is an important read, because when summed up quickly and succinctly the bottom line goes something like this: The current form of free trade agreements are structured so that the wealthiest maintain solid advantage and the poorest are forced deeper into poverty. Patricio Aylwin, former President of the Republic of Chile, said the following at the opening ceremony of the Thirty-first session of the FAO Conference where he was delivering the McDougall Memorial Lecture, in honor of Frank McDougall, one of the founders of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO).

Like many issues in global health, poverty, and development, there is no quick soundbite that can completely and accurately sum up the issue without sounding extreme. In a take-my-word-for-it manner, I can sum it up in this way: free trade agreements offer opportunities and protections for multi-lateral corporations that extend far beyond issues of ‘trade’ (here is a video that discusses some of the non-trade issues involved — transcript); free trade agreements disproportionally impact women; free trade agreements further impoverish the rural poor; free trade is often tied to structural adjustment programs, which push countries deeper into neoliberal economic policies that further cripple their poor populations; and finally, that the economic ideologies that dominate World Bank, IMF, and G8 policies are misguided and misreported. I included a few links that I felt offered relatively short and concise insight into those issues, although the true reading list into these issues is much greater in both length and density.

Instead of offering an economic debate (I spent a good 10 pages of my doctoral comprehensive exams on this, if you are really desperate on my own words), I thought I’d offer a personal account.

When I was working in Honduras in 2003 and 2004, I spent a lot of time traveling to remote villages in the mountains to talk to parteras (traditional birth attendants). Many of these meetings were pre-arranged, with parteras coming from even more remote areas to gather supplies and attend the trainings and focus groups we conducted. It was common for us to bring bags of USAID grain along for the ride to be distributed in these areas… bags of USAID grain, which had been grown and processed in the United States, and then shipped to remote farming communities in Honduras which were surrounded by fields of grain and legumes. What was happening??? Well, the value of the food those farmers were producing had dropped considerably. Families were forced to sell all that they could grow into order to survive… which meant that they had less food than they needed to live on. So although they were growing food, they had to sell more and more of what they grew in order to survive — and in very real terms, one season of drought could literally destroy their family. Their poverty wasn’t just a hard life, it was a live-or-die situation. The economic forces of structural adjustment and free trade amounted to growth in the country’s export, yes — because families had to produce more in order to compete. But at the cost of their own health and well-being. International trade advocates and financial institutions would call this situation a success because of the increase in export goods. The cost to the poor is not part of their equation.

Delivering those bags was a huge reason I decided to go for the PhD in International Health and Development. I realized in a very real and personal way that the ways in which we approached Global health and issues of poverty were skewed unfairly, and as a citizen of the United States, I felt obligated to at least try and do something about it.

Here are some pictures of us at a clinic delivering those bags in the mountains of north central Honduras (note the “USA” visable on the bags).

Following the lead of Alejna, who got it from Magpie, I will donate $2 to the International Forum on Globalization for every comment made on this post in the next 3 days (until Sunday at midnight — just in case others are late on this, too).

A day late, but better late than never.

Pennies for peace

I recently read Three Cups of Tea, the story of Greg Mortenson and his years of working in remote Pakistan and Afghanistan, building schools for some of the most impoverished children in the world. As a professional in the field of health and development, I was struck by the innocence with which Mr. Mortenson approached the monumental challenges inherent in this field with little support and no training; naively equipped with only respect and kindness in his heart. Part of the importance of the book is that it clearly demonstrates how the impoverished are easy targets for extremists, who offer free education, housing, and meals to people faced with no other life-sustaining options. In the area of the world forgotten by American aid and blanketed with US bombs, Greg Mortenson helps communities build schools and provides possibly the only light of American kindness seen by these people. The book passionately describes the beauty of the land, the people, and the compassion within of each community. It gives example after example of how, no matter the differences in our cultures or religions, we all want the same opportunities and happiness for our loved ones.

In that spirit, I encourage anyone who wants to honor the anniversary of 9-11 to visit the Central Asia Institute’s website, read about how their programs fight terrorism in it’s root causes, and make a tax deductible donation to this wonderful nonprofit.

UPDATE: This post was named a JUST POST for September 2008. (Thank you, Alejna!)